Dreamwork

the unconscious dances

It’s a movement meditation class. I am dancing and thinking about the difference between set dances (the learned choreographies of formal, ceremonial, and performative steps and styles) and the pedagogy of free form dance as an exploration and enactment of felt sensing from moment to moment, necessarily improvisational, changefully impelled and propelled. Like free association in psychoanalysis, free form dance is a working-through. The unconscious dances. A minimum of form and intentionality can produce infinite variations of open-ended speech or movement. When synchronization or harmonization happens in the group, it is only sometimes expressed mimetically. A kind of wild harmonization occasionally occurs in which everyone is doing something different, and yet entirely synched.

I am hot. I lean out a window in search of cool air. The window looks onto an alley. My eyes are pulled to my right; there is a battered, mildewed book on the far outer ledge of the windowsill.

How did it get there? Why would someone place a book on the far side of a windowsill of a building looking onto an alley 100 feet up from the street, where no one would ever find it, by what will? Had the book ever been seen by anyone before, after it was put there, why by whom, nothing but a wall across the other side of the narrow alley? A book, once dry in someone’s hands, now sat on a shelf in space, waterlogged and abandoned, out of context, cut loose and unanchored, precarious and decayed, become visceral, elemental and dank, its pages like wings stuck together, its cover an anamorphic blur, getting used up as material. What is abstraction but this: anything can become a context over time, because time itself is the movement of context.

(Now I think I know: a child put it there.)

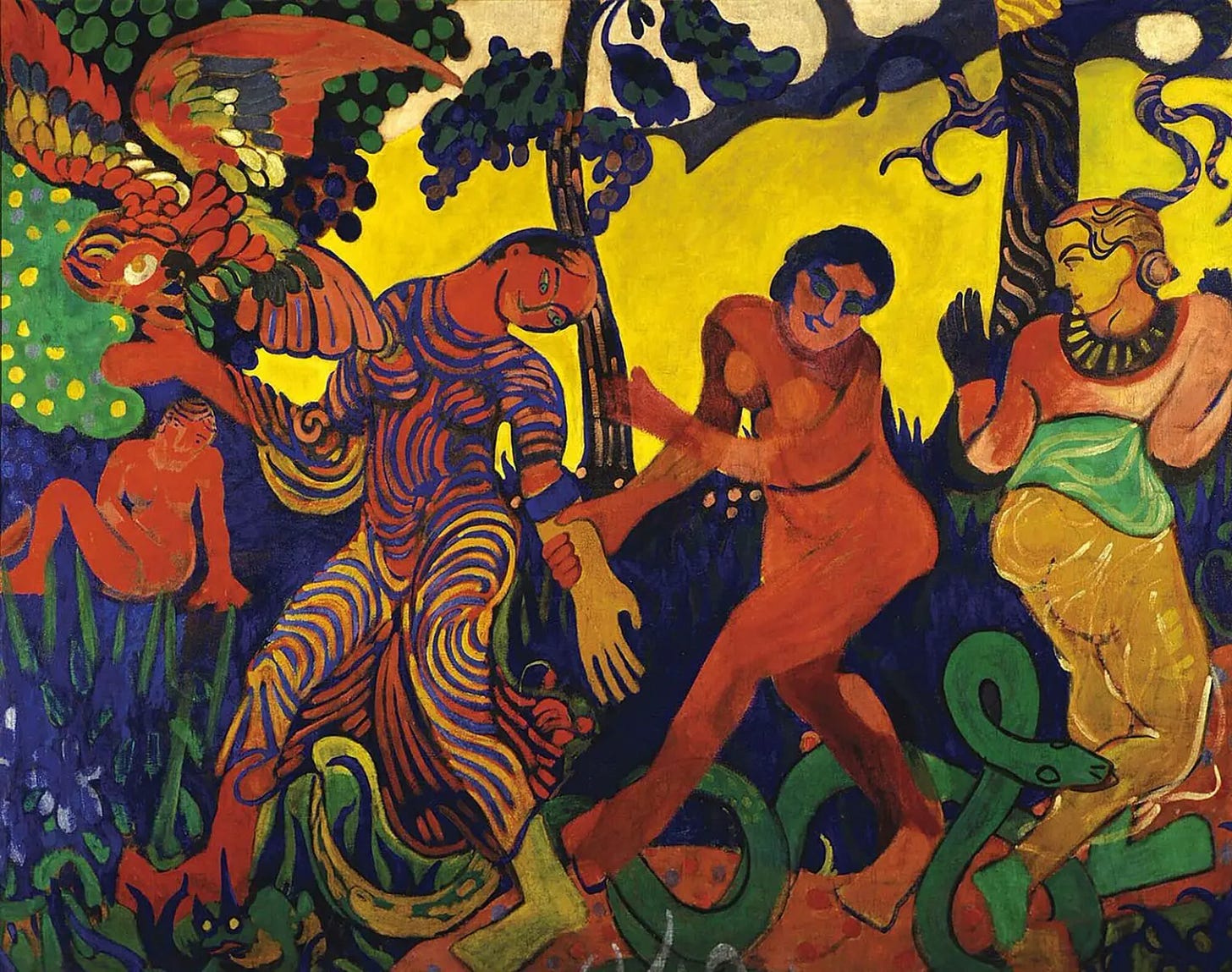

Painting by André Derain, La danse (1906)

Such an indescribably beautiful dream last night, landscapes and people singing a song that blasted across a desert with a melody I can still hear perfectly. The chorus, repeated in a groaning, longing shout, a conjuring: Ohhhhhhhh . . . Luddites!

Later in the dream I am traveling, there are old pieces of bread in my luggage, a friend decides to give away three spinets. I take one of them to use as a table. I wash it off. It’s exquisite, intricately blue metal.

I use many other terms that I don’t particularly like, such as “Dreaming” (which is a mistranslation and misinterpretation), because a lot of the old people I respect, and who have passed knowledge on to me, use these words. It’s not my place to disrespect them by rejecting their vocabulary choices. I know and they know what they mean, so we might as well just use those labels. In any case, it is almost impossible to speak in English without them, unless you want to say, “suprarational interdimensional ontology endogenous to custodial ritual complexes” every five minutes. So “Dreaming” it is.

— Tyson Yunkaporta, Sand Talk (New York: HarperCollins)

Through the dreams you can go there, you can go and receive the teachings of the five Buddha families. Through art you can contact the Buddha worlds . . . Some [people] can go anywhere in the universe and they can learn things from dreams, and they can bring this back. Buddha talked about this 2,500 years ago; there is no distance, everything is connected.

— Dalai Lama, Sleeping, Dreaming, and Dying (New York: Wisdom Publications, 2002)

I think some people have cleaned their minds. Their minds are light and they become psychic and they see things that are going to happen.”

— Lama Lhanang Rinpoche, in conversation with Jayne Gackenbach

I want to call into question the presumption that all dreams are inherently linked to the psyche.

— Amira Mittermaier, Dreams That Matter

Much of what we in the West call psychological and locate in some sort of internal space (‘in the head,’ ‘in the mind,’ ‘in the brain,’ ‘in consciousness,’ ‘in the psyche’) is understood in many cultures in manifestly nonpsychological terms and located in ‘other spaces.’

— Vincent Crapanzano, Hermes’ Dilemma and Hamlet’s Desire: Essays on the Epistemology of Interpretation (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992)

To add to the commonplace from elsewhere in my reading today (Thomas Ogden's "Bion's Four Principles of Mental Functioning"), since it felt lucky, and to think through a contradiction:

"The work of dreaming, for Bion, is the psychological work by means of which we create personal, symbolic meaning thereby becoming ourselves. In other words, we dream ourselves into existence. In the absence of the capacity for dreaming, we are unable to create meaning that feels personal to us: we cannot differentiate between hallucination and perception, between our waking perceptions of others, and between our dream-life and our waking-life. . . Dreaming is not a product of the differentiation of the conscious and unconscious mind; it is the dreaming that creates and maintains that differentiation, and, in so doing, generates human consciousness."

and "Dreaming occurs continuously both while we are awake and asleep. Just as the stars remain in the sky even when their light is obscured by the sun, so, too, dreaming is a continuous function of the mind that persists even when our dreams are obscured from consciousness by the glare of waking life."

In this piece Ogden also discusses Bion's idea that "it takes two minds to think one's disturbing thoughts," so perhaps Crapanzano's idea of "other spaces" where dreams occur (outside of the internal mind) wouldn't be too hard to reconcile with Bion's & Ogden's (at least two minds already) thinking.